“There’s No Free Lunch in Drug Development”

– Quin Wills on Tackling the Liver Knowledge Gap

“Science is hard, but getting the people formula right can be harder,” according to Quin Wills.

The founder and CEO of Ochre Bio is just as likely to talk about culture and values as he is about sequencing data or perfused livers. That balance – the rigorous science and the human side – has defined his journey from clinician in South Africa to leader of a company named on Hlx’s Brain Belt 50 report.

For Quin, reshaping liver medicine means building both brilliant science and the teams capable of carrying it through.

Quin, congratulations on making Hlx’s Brain Belt 50 list!

Thank you. I’m very proud of the team. One of the biggest learnings in my journey is that you need to get the science right first, but ultimately it’s all about the people.

Could you share some pivotal moments that shaped your journey into biotech?

That’s always a dangerous question to ask a founder; we tend to give you our life story! But I’ll try to keep it focused.

At heart, I’m a clinician and a geneticist. I began my training in South Africa, and very early on was drawn to thinking about the liver. Under apartheid, there was something called the “DOP system,” which meant it was legal to pay people in alcohol. In wine regions like the Cape, this created deeply impoverished communities having unhealthy relationships with alcohol. The impact was devastating: entire communities with extremely high levels of fetal alcohol syndrome.

That situation started me thinking about the genetic determinants of alcohol related traits – and to cut a long story short, it pulled me into liver research. People often think of liver disease as a first-world problem linked to drinking or obesity. But the truth is chronic liver disease disproportionately affects vulnerable communities worldwide.

The second big moment for me came with the Human Genome Project in the early 2000s (I’m showing my age now!) but like many geneticists at the time I was captivated by the promise of digitising human biology and causality. The rhetoric was “finally, we’re going to develop great drugs.”

I moved to the UK, retrained at Oxford-Cambridge, did extra degrees in maths and computing, and eventually a PhD in what we’d now call AI/ML applied to complex traits. And through all of that, the liver stayed my focus.

My first company was a liver genomics company. Later I set up and ran the Advanced Genomics department at Novo Nordisk – which, under the hood, was a liver team. Those experiences set the foundation for what I now see as my third pivotal moment: realising that after 20 years of digitising human biology, we still weren’t seeing the flood of drugs we’d been promised.

Were we too ambitious? Do we lack the right tools? What’s going wrong?

As a clinician at heart, I care about one thing: making medicines that impact patients. And for me, in liver disease, there are three things you must do exceptionally well:

-

Big, causal, high-quality human datasets for target discovery.

We know more about the brain than we do about the liver. Liver biology is far behind, so Ochre has invested heavily – over $20 million – to generate global liver sequencing and disease atlases. That enables us to do truly causal discovery in human biology.

-

Human validation models, so we can stop using mice.

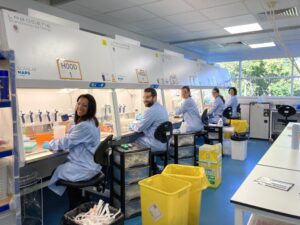

Mice are terrible validation models for liver disease. So we doubled down on building better options. Today, Ochre has over 25 first- or best-in-class human models – from primary human cell co-cultures and disease tissue cultures to whole perfused human livers in New York. It’s expensive and difficult work, but it’s the only way to know how therapies will behave in humans before clinical trials.

-

Translation into patients.

Discovery and validation aren’t enough… we have to find ways to improve a potential drug’s path out of the lab into clinical trials and finally to the patient. For example, we have never believed the rhetoric that tech-bio should be “biology only” and modality-agnostic. Why would you unnecessarily stack biology risk and chemistry risk together in clinical trials? So we built a strong RNA chemistry team. That way, we’re developing our own therapies in-house, speeding up R&D with a modality that works well as a liver therapeutic.

There’s no free lunch in drug development. If you’re serious about impacting human health, you have to do all three parts properly.

You completed degrees at both Oxford and Cambridge. Why did you choose to base yourself in this region?

If I had one piece of advice, it would be: embed yourself in a place where you can truly grow and be celebrated. That goes beyond science.

As you might have noticed in some of my posts, I’m an openly gay man. For me, it mattered to be in a society that aligns with my values, where I can contribute authentically. That’s why I settled in the London-Oxford-Cambridge triangle.

Looking five to ten years ahead, where do you see your work impacting patients’ lives and the biotech landscape?

I love numbers, so let’s start there. Every year, at least 1.5 million people die of chronic liver disease. For most of them, the only curative option is a liver transplant.

Yet globally, there are only around 40,000 transplants a year. Medicine, in that sense, becomes a health lottery. What drives us at Ochre is changing that.

What’s the single biggest challenge in translating science into real-world applications?

People. Science is hard, but getting the people formula right can be harder.

A mistake I made with the first company I founded was over-focusing on scientific excellence and underestimating how important it is to invest in people and operations. With Ochre, even before raising money, we defined our company values and committed to focusing on people. That foundation has been critical.

What qualities do you consider most important in leading a biotech?

I believe in situational leadership. My natural style is pace-setting: solve problems, move fast, get the minimum viable results. That works for scrappy startups.

But as Ochre has grown and we prepare for the clinic, my role has evolved into being the CEO (Chief Energy Officer.) We have outstanding people. My job is to keep us energised, focused, and aligned with our 2030 clinical vision.

And has stepping into the CEO role changed your day-to-day?

It’s amazing how quickly perceptions shift once the title changes!

Expectations are of course different. My day-to-day is now much more stakeholder-facing, but ultimately I focus on whatever makes the company successful. A large part of that is empowering others.

Ochre has scaled quickly across multiple regions. How has geography shaped your approach to building the right team?

Ochre is based in Oxford, New York City, and Taipei. That gives us interesting contrasts.

One example of a region-specific consideration was our deliberate choice not to set up in Boston, in part so that we could get the people formula right. Being in the major biotech hub that Boston is comes with its challenges – one of them being unusually high staff turnover for the next shiny biotech. That doesn’t work when perfusing human livers, which requires extensive training and skills continuity. On the other hand, New York has provided the same level of talent, and the same high-quality clinical networks. In exchange, Ochre has brought the world’s first ‘liver ICU’ to New York. I like to think that it’s been a good pairing that has helped build a wonderful scientific team wanting to hang around in what is a very exciting city to call home.

There are, nevertheless, universal challenges no matter the geography. For example, one global shift I’ve noticed is how many computational biologists are shifting into AI, making it increasingly tough to find the skills and passion required for generating high quality data sets. Unfortunately, without great data we don’t have great AI.

Biotech is a notoriously challenging market. How do you steer through the tougher times?

Having strong company values is one good way to surf the spaghetti that is the biotech world. At Ochre, our values are built around flourishing through failure. After 20 years of leading teams, I’d say the defining feature of success is how you handle failure. We break it into three parts:

- Clarke’s Law: Don’t fear failure. Be ambitious. Venture-backed biotech isn’t about incrementalism.

- Murphy’s Law: Expect setbacks. Biology is failure after failure, then learning, then success. Iterate quickly.

- Wheaton’s Law: Don’t be a dick. No tribalism, no blame-shifting. Own mistakes, learn, and support each other.

Those values have served us well in science, in building the company, and in life.

Final question. How do you balance leadership demands with maintaining your passion for science?

I’m ashamed to admit that just yesterday I derailed a leadership meeting because I got excited about a new computational paper from a colleague! I still read papers, and every Monday morning I send the company an email about something interesting I’ve come across.

For me, the scientific spark is what keeps everything else alive. It’s such a privilege to be around at a time of our species’ journey where scientists can help shape that journey.

Quin and Ochre Bio were recently featured in the Hlx Life Science’s Brain Belt 50 report, spotlighting 50 founders and scientific leaders driving life science innovations across the UK’s brain belt.